The caged bird sings with a fearful trill of things unknown but longed for still and his tune is heard on the distant hill for the caged bird sings of freedom.

— Maya Angelou, Caged Bird

The most exhausting thing in life, I have discovered, is being insincere. That is why so much of social life is exhausting; one is wearing a mask. I have shed my mask.

— Anne Morrow Lindbergh, Gift from the Sea

The act of stepping away in the digital age feels like abandoning מִגְדַּל בָּבֶל built on the collective ambitions teetering under the weight of its own chaos1.

I once believed this structure was indispensable.

Now I wonder if it is not a mausoleum for the soul, if the soul even exists2.

The paradox of connectivity

Once heralded as the great unifier, the exalted promise of digital connectivity has become an unrelenting labyrinth, where identities dissolve into refracted echo-chambers of recursive entanglements of selfhood unspooled.

In The Book of the City of Ladies, Christine de Pizan’s walled sanctuary wove women’s fortitude beyond the discord of prescriptive mores:

Dear daughter, do not be afraid, for we have not come here to harm or trouble you but to console you, for we have taken pity on your distress, and we have come to bring you out of the ignorance which so blinds your own intellect that you shun what you know for a certainty and believe what you do not know or see or recognize except by virtue of many strange opinions (I.2.1).

Christine de Pizan provides a traditional refuge from the world disconnected by the noise of societal expectations, where strength is forged in the furnace:

Have you forgotten that when fine gold is tested in the furnace, it does not change or vary in strength but becomes purer the more it is hammered and handled in different ways? Do you not know that the best things are the most debated and the most discussed? (I.2.2.)

It’s similar to the woven digital structure intersecting network connections that promise unity often in the essence of what it means to be whole, i.e., individual strength, societal pressures, and self-reflection.

Before the connectivity of the internet, The Life of St. Mary of Egypt drowned the cacophony of voices, harrowing the desperate waiting for a sojourn found within a sanctuary.

Emerging not as withdrawal but an abdication to reclamation, something powerful was experienced:

An awful Dread ſeized her, at firſt, upon her Entrance into the Sanctuary; ſhe, however, approached the Holy Wood; ſhe reverently worſhiped it, and at the ſame Moment found her Soul repleniſhed with an unexperienced Lightneſs of Heart, an aſſured Truſt of GOD’s gracious Pardon of her manifold Sins and Abominations, and an interior Conſolation which ſhe had never felt before.

She returns to the Place where the bleſſed Virgin's Picture was fixed; ſhe a ſecond Time proſtrates before it, giving the Mother of GOD reſpectful and grateful Thanks for the Favour juſt obtained thro' her Interceſſion; and having found her already ſo efficacious an Advocate in her behalf, ſhe entreated her to continue her powerful Influence at the Throne of Mercy, by letting her know the Divine Will, where and how ſhe was to accompliſh her promiſed Repentance. (15-16)

St. Mary of Egypt’s passage unlit corridors of exile clarified to distill itself, freed from distractions where our fragmentary selves knit together stillness in the space of clarity:

No one could have more Experience of all the diſmal Effects of the Tyranny of Love than Mary; and no one, on her becoming a Penitent, could be more ſerious, determined and ſucceſsful, in getting out of its cruel Thraldom.

She flew into the Deſart from its treacherous Embraces: She prayed inceſſantly to be delivered from its cheating Illuſions; and a rigorous Penance was made to atone for a Life of Softneſs, Delicacy and Pleaſure: Yet even ſo ſhe was not exempt from Love's furious Aſſaults: It purſued her into her loneſome Solitude, and beſet her with all its wily Artifices, and the whole Strength of its Forces; but in vain: Mary ſtood her Ground, immoveable as a Rock; nothing diſmayed at the frightful Proſpect of theſe many and troubleſome Conflicts.

Merciful, all-ſeeing Providence, that had appointed the Deſart for her Field of Battle, in conducting her thither, was her Comfort and her powerful Support.

The Remembrance of the Flames of Hell, to which ſhe deemed herſelf, for her manifold Sins, the deſerved Victim, contributed to ſtifle the Flames of Concupiſcence. (21-22)

Self-worth is fleeting when connection is isolation—we must remember, fragments can be stitched together.

St. Mary of Egypt's journey, as if heretical, questions the sanctity of progress itself, an act of rebellion glimpsed in The Book of Margery Kempe.

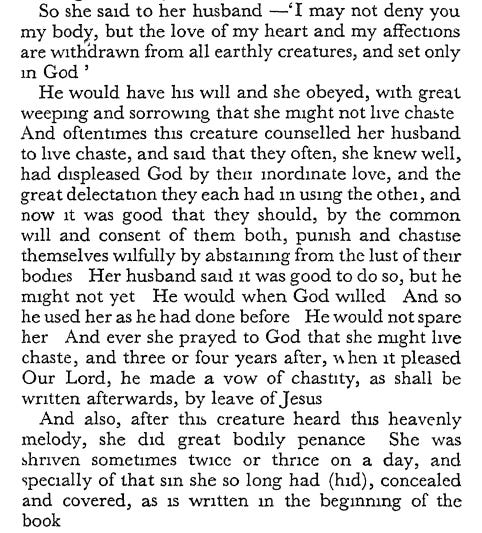

Her mystical experiences often came when she withdrew from the world and sought solace in prayer, struggling with the expectations of a society that demanded she maintain an outward appearance of piety and relevance:

Free from bodily desire yearned deeper connection.

Disjointed, the perpetual entanglement we see within is a quality within the purview of the divine, often what lays before our own eyes.

Such Sisyphean yoke leaves us in need of being unplugged, for our sanity becomes ouroboric scrutiny; for our normative abstinence, holding inabilities inescapable to feedback loops, formulate the basis of the fragmentation of ourselves, a leviathan we created.

Many of us find ourselves tethered to the experience of losing oneself in the noise of the world.

The irony lay in how these incessant interruptions left us fragmented, unable to fully inhabit the present.

In an era of relentless digital immersion, true understanding emerges only in the silence of deliberate withdrawal: the sanctified renunciation severed the sinews of earthly expectation to glimpse the ineffable.

Psyche | Noumenon | Amina | Geist

If the unseen lingers upon the marrow of being, does the soul wane into presence upon the void’s own forgetting?

Julian of Norwich’s Revelations of Divine Love offers a striking perspective:

Beneath the life of those senses which reveal to us that world of appearances, which the unreflecting so easily confound with the reality which it only symbolises; beneath the life of the understanding, whose forms and frames (contrasting in their permanence and universality with the unsteadiness and uncertainty of that chaos of fleeting phenomena which they but classify and set in order) have seemed to some to merit the name of Reality; beneath even the life of the higher, though self-centred and self-regarding emotions and sentiments, aesthetic or spiritual; deep down at the very basis of the soul, is to be sought the only life that in an absolute and independent sense deserves the name of "real," because by it alone are we brought into conscious relation with other personalities, and made aware of our own. (v-vi)

Thus, beyond the ephemeral reflections of perception, the psyche itself may be sincerity incarnate, breathing between the corporeal and the ineffable, suspended in the whorls of consciousness warped by ever-receding mirages.

Does thought substantiate being, or merely conjure its own ghost?

Is the self a recursive whisper in the hollows of cognition?

‘Cogito, ergo sum’ wavers to the Phantomgeist of each synaptic chiaroscuro suspended between eidetic apparition and neuronal connectome, as the noumenon lingers at the trembling precipice within the vestigial flicker of its own unfathomed becoming3.

St. John of the Cross lays it bare in The Ascent of Mount Carmel:

In a dark night, With anxious love inflamed, O happy lot ! Forth unobserved I went, My house being now at rest. In darkness and in safety, By a secret ladder disguised. O happy lot ! In darkness and concealment, My house being now at rest, etc. (1)

The dark night through which the soul must pass toward divine light is an abyss that no words can fully articulate—one can only endure it.

Is this the birthing pang of a new Logos, unmoored from flesh bound to the relentless teleology of its own irreducible specter of mind and spirit?

In this descent, the essence of selfhood is flayed before the unshakeable radiance of the divine, revealing truth beyond the limits of perception, transmuting the spiritual materialism forged in struggle, where mind and matter cease to be opposed as expressions of singular substance, an emergent consequence of labor4.

As Piers Plowman warns:

Beguile not thy bondman, the better thou'lt speed ; Though under thee here, it may happen in heaven His seat may be higher, in saintlier bliss, Than thine, save thou labour to live as thou shouldst ; Friend, go up higher (Luke xiv. 10). (VI, 46-49)

In the realm of apophatic theology, the Pneuma Theou circumambulated via mystagogia negation sempiternal to what cannot be said about the ineffable nature of God.

As the divine paradox lies in the axiomatic postulation that sophia arcana emanates as a vestige of the Absolute, perceiving and receiving the boundaries of sensorial apprehension within the confines of epistemes reach forms docta ignorantia, in a manner beyond human perception.

This invites seekers into omphalic axis, with Arcanum Absolutum surpassing our architecture of intellect.

The ‘Garden’ as a metaphor…

Are we trembling in fear of the eternal Nous?

The garden, in its many iterations, is a site of paradox, from sacred enclosures to surrealistic spaces of psychological fragmentation, the garden is a palimpsest of human aspirations, anxieties, and transcendental yearnings.

It’s the site of divine plenitude and irrevocable exile, i.e., Hortus Conclusus5.

In The Garden of Cyrus, Sir Thomas Browne perceives the garden as an expression of divine harmony according to the quincunx:

In garden delights’ tis not easy to hold a mediocrity; that insinuating pleasure is seldom without some extremity. The ancients venially delighted in flourishing gardens; many were florists that knew not the true use of a flower; and in Pliny’s days none had directly m treated of that subject. (77)

Where the untamed wilderness threatens the psyche’s cultivated consciousness, the aetatis spiritus sancti envisions a quincuncial order, as stated by Socrates in Phaedrus, where one can either bear fruit or decay into disorder:

Would a sensible farmer, who cared about his seeds and wanted them to yield fruit, plant them in all seriousness in the gardens of Adonis in the middle of the summer and enjoy watching them bear fruit within seven days? Or would he do this as an amusement and in honor of the holiday, if he did it at all? Wouldn’t he use his knowledge of farming to plant the seeds he cared for when it was appropriate and be content if they bore fruit seven months later? (276b)

In contrast, Schwaller de Lubicz’s alchemical interpretation of the garden aligns more closely with the wise farmer’s understanding, presenting a space measured in intentional action6.

Whatever ambient figure the garden is, the perennial dialectic within its -verdant and ruinous thresholds—of cosmos and chaos, discipline and fecundity, labor and grace—lingers not as a relic of loss or promise of reclamation.

It’s found in the farmers who understands when to plant, and reap what they’ve sown.

“Better the devil we know, than the desert we don’t”

The voice of the unheard silences emptiness in the margins, asserted by Blake as dismantled illusions of binary opposition, where energy and restraint, fire and form, are necessary forces shaping existence.

In The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, the unheard voice is not an anomaly but a catalyst, pressing against imposed structures suppressed by stagnation:

Without contraries is no progression. Attraction and repulsion, reason and energy, love and hate, are necessary to human existence. From these contraries spring what the religious call Good and Evil. Good is the passive that obeys reason; Evil is the active springing from Energy. Good is heaven. Evil is hell. (7)

Yet, humanity clings to familiarity, fearing the uncertainty of the unknown:

“It’s better the devil we know than the desert we don’t7.”

Blake’s rebellious fire does not offer comfort, but calls for departure from the known into the uncharted desert, brimming with hidden potential.

Carl Jung’s Mysterium Coniunctionis and the alchemical wisdom of Gerhard Dorn affirm this hidden potential, encapsulating the philosophia perennis of the soul’s struggle toward higher understanding which reveals wisdom as either an illuminating panacea or a consuming poison.

The process of individuation requires the interplay of light and dark, Hermes and Aphrodite, Logos and Eros, lest the fire-point at the soul’s center become shadowed:

For them the dark side of the world and of life had not been conquered, and this was the task they set themselves in their work. In their eyes the fire-point, the divine centre in man, was something dangerous, a powerful poison which required very careful handling if it was to be changed into the panacea. The process of individuation, likewise, has its own specific dangers. Dorn expresses the standpoint of the alchemists in his fine saying: “There is nothing in nature that does not contain as much evil as good.” (59)

The moon, as a symbol of individuation, embodies the reconciliation of opposites, where both mother and spouse of the sun carry the spagyric embryo (i.e., the Self), as the anima personifies the collective unconscious, containing the six planetary spirits of the metals.

Individuation demands this sacred conjunction, where intellect alone cannot replace the soul’s ascent through shadow and revelation:

The moon with her antithetical nature is, in a sense, a prototype of individuation, a prefiguration of the self: she is the “mother and spouse of the sun, who carries in the wind and the air the spagyric embryo conceived by the sun in her womb and belly.” This image corresponds to the psychologem of the pregnant anima, whose child is the self, or is marked by the attributes of the hero. Just as the anima represents and personifies the collective unconscious, so Luna represents the six planets or spirits of the metals. (157)

It is here, in the sacred Hierogamía, that λόγος and ἔρως (Logos and Eros), corpus et spiritus, οὐσία and μὴ ὄν (Being and Non-being) are bound in mystical union, as lucifer ascendet ab abyssus maris; and, so too does the Nous, rising from the hidden depths of the unconscious.

This diurnal procession against lux et nox is a primordial anacyclosis, wherein Prometheus’ phantasma contends with the abyss, only to return in an inexorable omnia mutantur, nihil interit.

Thus, the great Sophia lights the fires marking the psyche’s journey (an iter sapientiae), where the breath of life mediates the refined struggle within the hidden self (homo absconditus), as both materia prima and lapis philosophorum, the bride of the coniunctio oppositorum: the shattered Imago Dei retrieved per ignem, per aquam, per aerem, per terram.

And so, quod est inferius est sicut quod est superius declares the adept must descend into umbrae profundissimae, unearthing the final syzygy, no longer spoken ex cathedra, but known, utterly, within:

ἡ ὁδὸς καὶ ἡ ἀλήθεια καὶ ἡ ζωή (John 14:6)

אֶֽהְיֶ֖ה אֲשֶׁ֣ר אֶֽהְיֶ֑ה (Exod. 3:14)

If the desert beyond the known is not a barren exile but the crucible where the soul is remade, will you remain a silent witness to your own undoing?

If the voice of the unheard is a smothered ember, aching to unfurl into a pyre, will you unbind the fire, let it rise, and burn a path toward the infinite?

Also, it is awaiting divine intervention, i.e., the Etemenanki of Jubilees 10.

The ontological and epistemological status of the soul, remains a subject of intense scrutiny across multiple disciplines.

Cartesian dualism, which framed the soul as an autonomous, non-material substance capable of independent existence from the body, has been increasingly challenged by materialist and physicalist perspectives.

From a contemporary naturalistic standpoint, the soul has been largely reframed as an epiphenomenon of complex neural dynamics, particularly dominant within cognitive neuroscience (i.e., the theory of integrated information).

From a metaphysical perspective, however, consciousness—or the "soul" as a persistent, transcendental form of subjectivity—may not be confined to human experience but instead constitute an intrinsic feature of all matter, wherein even subatomic particles exhibit rudimentary forms of experience.

In religious and philosophical contexts, the soul is often viewed as the immaterial essence of a human being, conferring individuality and humanity.

Thus, the question, therefore, remains whether the soul exists as a postulated metaphysical entity, a byproduct of emergent properties in cognitive systems, a dimension of subjective experience that defies reductionist explanation, or perhaps some thing beyond explanation.

Despite extensive inquiry, no empirical evidence has conclusively substantiated the existence of an immaterial soul, nor has any scientific framework effectively addressed the "hard problem" of consciousness.

The self, suspended between eidetic apparition and neuronal phantom, echoes Freud’s tripartite psyche—where the id’s primordial murmur collides with the ego’s regulatory lattice and the superego’s societal inscription.

Jung dissolves these distinctions, weaving selfhood into the Mnemosyne-laden fabric of the collective unconscious gesturing towards the Anima Mundi, ensouled by the Logos.

Neuroscience threads thought, matter, and form into an ephemeral cartography of symphonic dissolution, rendering onto the connectome a metaphysical tableau where identity is neither fixed nor singular, but an emergent maturation of synaptic flickers.

Implicated in self-referential thought, the default mode network (DMN) grounds and destabilizes selfhood, oscillating between introspective recursion and the specter of Nagarjuna’s śūnyatā—emptiness not as negation, but as the trembling vestige of being’s unfathomed becoming.

Much like wavefunctions in quantum mechanics where the act of observation collapses possibility into being, this wavering finds itself in epistemological kinship with the noumenon, an event that exists only insofar as it is observed; an irreducible opacity dissolving into the unknowable void, neither empty nor full.

The קול הבריאה (kol ha-beriah) over the waters above and below wretch itself in self-consciousness, negotiating spirals of the unfolding telos synthesized in the ascent of Prometheus’ Geist.

The primordial utterance over Mayim Elyonim (the upper waters) suspended above Tehom (the fathomless deep chaos), is where the bat kol (‘daughter of voice’) presents a prophecy by divine articulation, cleaving order from the void (Genesis 1:6-7; cf. Deuteronomy 4:12).

The Song of Songs 4:12-15 enshrines the גַּן נָעוּל (Gan Na’ul), a sanctuary of divine intimacy enclosed in numinous and terrestrial coalescence, veiled yet fecund, sacred yet sensuous:

My sister, my spouse, is a garden enclosed, a garden enclosed, a fountain sealed up.

Thy plants are a paradise of pomegranates with the fruits of the orchard…

The fountain of gardens: the well of living waters, which run with a strong stream from Libanus.

Divine love flourishes beyond the profane Theotokos, whose sacred womb became the enclosure in which the Logos germinated; the fountain gardens of the living waters symbolic of the Pneuma’s renewal, as in Revelation 22:1-2.

Libanus prefigures the eschatological renewal of Eden, where the garden, no longer a relic of loss but a prophecy of restoration, is ceaselessly irrigated by the Spirit’s grace, as the four rivers once nourished the primeval sanctuary.

The soul’s apotheosis—altar and tomb, bridal chamber and philosopher’s stone, Eden lost yet ever reclaimable—is not a place but a state, where longing and receptivity render the self a fertile ground for the divine seed, nourished by wisdom’s eternal fountain, lingering in the luminous dusk of remembrance and renewal.

As St. Augustine affirms in Confessions:

…so a believer, whose all this world of wealth is, and who having nothings yet possesseth all things, by cleaving unto Thee, whom all things serve, though he know not even the circles of the Great Bear, yet is it folly to doubt but he is in a better state than one who can measure the heavens, and number the stars, and poise the elements, yet neglecteth Thee who hast made all things in number weighty and measure. (cf. 2 Cor. vi. 10, Wisd. xi. 20) (96)

And as Paradise Lost’s Adam and Eve step beyond Eden, they do not walk into mere loss but into the perilous grace of reorientation:

Some natural tears they dropt, but wiped them soon ; The world was all before them, where to choose Their place of rest, and Providence their guide : They, hand in hand, with wandering steps and slow, Through Eden took their solitary way. (Book XII, 645-649)

See The Temple in Man.

This theme appears in Jeremiah 2:13 and Isaiah 31:1, Arabic proverbs, André Gide’s call to abandon the shore for discovery, Dante’s Inferno, and Jungian thought, all emphasizing that resisting change may feel safe, but true growth lies beyond the known.