The world begins at a kitchen table. No matter what, we must eat to live.

— Joy Harjo, Perhaps the World Ends Here

“Do you mean to tell me that you're thinking seriously of building that way, when and if you are an architect?”

“Yes.”

“My dear fellow, who will let you?”

“That's not the point. The point is, who will stop me?”

— Ayn Rand, from The Fountainhead

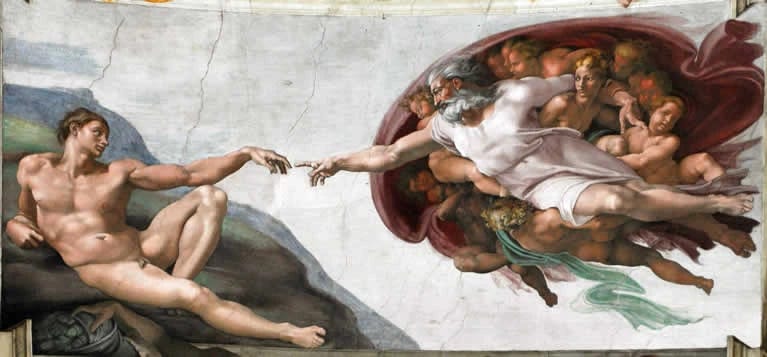

Belief is neither an arbitrary psychological phenomenon nor a singular construct reducible to one domain of human experience.

It’s an emergent property of cognition, intricately shaped by neurophysiological architecture, social conditioning, and metaphysical intuitions, existing trans-dimensionally to span physical, psychological, and theological realms.

Some initial questions are raised:

What neurobiological and psychological mechanisms generate belief?

How does belief relate to epistemology, perception, and the nature of reality?

How do historical, mystical, and doctrinal traditions shape and sustain belief?

What theories challenge belief’s necessity or validity?

The neurobiological genesis of belief

What neurobiological and psychological mechanisms generate belief?

Belief is an intrinsic feature within human cognition, manifest across religious faiths, scientific paradigms, and assumptions about reality1.

Belief formation is not an arbitrary cognitive artifact but an emergent neurobiological necessity, arising from the predictive processing framework instantiated in cortical-limbic circuitry2.

According to Karl Friston’s Free Energy Principle (FEP), the brain operates as a hierarchical Bayesian inference system, continuously minimizing free energy (a measure of surprise or uncertainty) by constructing and updating generative models of the external world3.

Under this framework, belief is not a passive registration of reality but an active construction designed to optimize predictive coding, as the cortical hierarchy refines probabilistic representations through recursive Bayesian updating, ensuring that perception, cognition, and action remain dynamically attuned to environmental affordances.

Consequently, this structuring allows ontological engagement with external surroundings, serving as basis for such neurophysiological phenomena as the hollow mask illusion4.

As such, belief is both inevitable and evolutionarily advantageous, serving as the cognitional dominance of deeply ingrained priors over raw sensory data, which reality itself is actively constructed and sustained5.

This exemplifies the inference-driven nature of perception, wherein belief structures override veridical sensory input to preserve cognitive coherence within individual and social dynamics6.

The fractured foundations of “knowing”

How does belief relate to epistemology, perception, and the nature of reality?

Belief is irreducibly complex, construed between epistemic perception and realities cognition—neither fully subjective nor entirely objective—within Ding-an-sich7.

This creates a paradox of ‘sorts’, as the epistemological tension between Scientia and opinio vulgaris remains a troubling dilemma, making knowledge subject to collapsing into itself.

In other words, it’s an epistemic illusion shaped by sensory deceptions and cultural contingencies, situated within the structural perception of our limited access to phenomena rather than noumena8.

Knowledge must be justified through true belief, yet this filters perception and constrains epistemic fluidity, rendering objectivity neurologically contingent rather than absolute, thus instilling doubt by revealing what we accept as rational or true.

It is not shaped by pure logic but by the brain’s intrinsic biases, adaptive constraints, and interpretative frameworks9.

It is an ouroboric recursion intertwined to Bayesian inference, where prefrontal-limbic shaping lead the nous and psychē through an abyss into the kenotic plenitude of Being, dissolving the individuated ego like a chrysalis toward metamorphosis10.

This pilgrimage is a mystical surrender—neither an arbitrary projection nor a direct apprehension of truth—where dissolution of belief is between certainty and doubt.

Whether reflecting the external world (realism) or actively constructing it (idealism), belief remains a unifying force that shapes cognition ontologically and metaphysically, becoming a fundamental reality within nature itself.

The Alchemy of the Nous

How do historical, mystical, and doctrinal traditions shape and sustain belief?

Belief and faith, while related, are distinct:

belief is cognitive assent

faith is actioned belief

The Merneptah Stele (c. 1207 BCE) provides archaeological confirmation of Israel as a distinct people, yet their survival was not due to belief alone, evidenced in sociological resilience fostered under stress, leading to social cohesion and unified identity11.

This principle is similarly witnessed in theological linguistic adaptation.

The Letter of Aristeas documents Jewish scripture within Greek intellectual frameworks, expanding the notion of cultural evolution in religious belief systems.

Though, belief alone does not compel action, faith does, as the believer does not choose belief as much as belief chooses the believer12.

To believe is to partake in a Ridderen af Troen, the sacred negotiation in which credo contends with mysterium, burning linguistic coals stoked in exile’s return, as the Roman’s recognition leaps beyond probability into the unknown13.

الحق ,האמת — τὸ ὄν, ens verum

What theories challenge belief’s necessity or validity?

Belief is neither an unshaken foundation nor an immutable law, but a living architecture—perpetually rising and collapsing, dissolving into paradox yet reassembling anew, at once affirming and eroding its own necessity14.

Yet does it reveal truth, or merely the architecture of human longing?

Thus, we stand within—where belief fractures as it binds, dissolves as it reasserts—leaving the question unresolved: was it ever necessary, or merely the name of our endless becoming?

Belief is neither doxa nor gnosis, but an ontological paradox within cognition, existing between negation (apophatic) and affirmation (cataphatic).

It functions as an a priori synthesis within Madhyamaka emptiness (cf. śūnyatā; Nāgārjuna, Mūlamadhyamakakārikā), meaning belief lacks intrinsic essence (svabhāva), existing only in relational dependence.

Historically, hylomorphic cosmology (Aristotle’s De Caelo) dominated until the Michelson-Morley experiment disproved the luminiferous Aether, shifting cognition towards Bayesian frameworks and unconscious inferences (cf. Unbewusste Schlüsse; Handbuch der Physiologischen Optik, 1867).

Neurologically, belief arises in the interplay of material and form (ὕλη-μορφή), where quantum indeterminacy replaces ontological fixity, allowing for numinous (divinely-inspired) self-perception.

Theologically, Augustine’s Fides quaerens intellectum parallels introspective processes in the brain’s precuneus, where mystical states and fiduciary illusions shape human perception of sovereignty.

Cicero’s emphasis on faith as the foundation of justice highlights its role in societal coherence:

Fundamentum autem est iustitiae fides, id estdictorum conventorumque constantia et veritas. (Cicero, De Officiis, I. vii, 23).

Philosophically, Heidegger’s thrownness (cf. Geworfenheit in Sein und Zeit, 135) and Sartre’s mauvaise foi frame belief as a metaphysical rejection of existential evasion, akin to Camus’ absurd struggle in Le Mythe de Sisyphe.

Ultimately, belief is a self-referential structure of human cognition, recursively generating certainty amid uncertainty—yet within science, it remains tied to empirical constraints.

Praecipuum centrum mentis est conditio sine qua non mimesis

Clark, Andy. “Whatever Next? Predictive Brains, Situated Agents, and the Future of Cognitive Science.” Frontiers in Theoretical and Philosophical Psychology, edited by Axel Cleeremans and Shimon Edelman, Cambridge UP, 2013.

Alexander, Garrett E., et al. “PARALLEL ORGANIZATION OF FUNCTIONALLY SEGREGATED CIRCUITS LINKING BASAL GANGLIA AND CORTEX.” Ann. Rev. Neurosci., vol. 9, Annual Reviews, 1986, pp. 357–81.

The architecture of the brain includes the prefrontal cortex (PFC) which orchestrates cognitive structuring, the limbic system (amygdala, hippocampus, nucleus accumbens) that encodes emotional and reward-based reinforcement.

The structural neuroplasticity of the brain, modulated by synaptic efficacy and neuro-modulatory systems (e.g., dopamine, serotonin, and glutamate), facilitates the reinforcement, adaptation, or extinction of beliefs in response to environmental stimuli and experiential contingencies.

Christopher L. Buckley, Chang Sub Kim, Simon McGregor, Anil K. Seth. The free energy principle for action and perception: A mathematical review, Journal of Mathematical Psychology, Volume 81. 2017. Pages 55-79. ISSN 0022-2496.

This reminds me of Michael Persinger’s “God Helmet” experiments, where electromagnetic stimulation of the temporal lobes induced religious-like experiences, reinforcing the idea that belief has a neurobiological basis within religious and mystical experiences.

I find similarity to this in predictive biases, when people see patterns in randomness (apophenia) or attribute intentionality to non-living phenomena (hyperactive agency detection).

Andrews-Hanna, Jessica R., et al. “The default network and self-generated thought: component processes, dynamic control, and clinical relevance.” Ann N Y Acad Sci, vol. 1316–1, journal-article, 2014, pp. 29–52.

Atran, Scott, and Ara Norenzayan. Religion’s Evolutionary Landscape: Counterintuition, Commitment, Compassion, Communion. pp. 713-770

The Default Network (DN), a system integrating the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), posterior cingulate cortex (PCC), and angular gyrus—as demonstrated in neuroimaging studies—serves as the neural foundation for internal simulations (self-referential thought), meaning-making (belief construction), and the perception of intentionality (autobiographical memory).

Such cognitive tendencies likely contributed to anthropomorphism and the emergence of religious beliefs, reinforcing the functional role of the DN in shaping existential interpretations.

See Boyer, Pascal. Religion Explained: The Evolutionary Origins of Religious Thought. Basic Books, 2001.

Boyer asserts that interacting with other agents requires “a social mind”:

This is crucial because the social mind systems are the ones that produce the great similarity between supernatural agents and persons as well as the crucial difference that makes the latter so important. (159)

Humans tend to postulate the presence of agents rather than their absence, making Voltaire’s account quite clear. i.e., a god is convenient (37).

Belfort (1883) points out Kant’s meaning behind the term Ding-an-sich:

The noumenon, or thing-in-itself, is the point of contact between “theory of knowledge" and ontology. In the critical philosophy it appears in three forms; I. as the unconditioned object of the internal sense; II. as the unconditioned object of the external sense; and III. as the unconditioned object in general, the ens realissimum or Absolute. (Kant’s Prolegomena, lxxxiii)

Medicus (1920) expands upon this, stating:

Alle Eigenschaften der Dinge sind in dem Sinne relativ, daß sie immer ein Verhältnis des einen Dinges zu andern Dingen, nicht aber etwas bedeuten, was dem einen Dinge an sich allein zukäme. (Grundriss der Philosophischen Wissenschaften, 85)

Thus, Ding-an-sich eludes complete assimilation into human cognition while shaping the boundaries of knowledge itself, i.e., a state between presence and inaccessibility.

Kennedy (1881) states:

Knowledge,…does not lie in the affections of sense, but in the reasoning concerning them: for in this it seems possible to grasp essence and truth, and not in the affections? (Theaetetus, 180)

This dilemma is formally articulated in Münchhausen’s Trilemma, introduced by Hans Albert.

Named after the fictional Baron Münchhausen who absurdly claims to have lifted himself from a swamp by pulling on his own hair, Albert used it to critique the problem of justification in epistemology, as the trilemma highlights that any claim to knowledge must ultimately succumb to one of three equally problematic modes of justification:

Infinite Regress (regressus ad infinitum)—Each justification requires a further justification, which itself must be justified ad infinitum, leading to an unsustainable epistemic chain.

Circular Reasoning (circulus in probando)—A belief is justified by another belief that ultimately relies upon the original claim, resulting in a tautological structure.

Foundationalism (axiomata prima, dogmatic axiom)—One must terminate justification by asserting an unproven fundamental assumption, contradicting the principle of justification itself.

Each of these resolutions fails to escape epistemic circularity, much the same way recursive limitation applies to belief structures.

If one attempts to justify skepticism, one is invariably relying on axioms or inferential systems that themselves require justification, i.e., belief in doubt is still belief (Ipse venenum, ipse salus).

This ouroboric recursion closely parallels Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorems, which demonstrate that any sufficiently complex formal system contains propositions that are true yet unprovable within the system itself (Gödel, Über formal unentscheidbare Sätze der Principia Mathematica und verwandter Systeme I).

Ultimately, the Trilemma reveals the recursive inevitability of belief, where all knowledge claims are infinitely deferred, tautologically enclosed, or arbitrarily postulated—such that skepticism itself becomes belief, sustaining the dialectic of knowing and unknowing.

Proverbs 8 affirms wisdom as the structuring force, aligning with Bayesian inference—an iterative recalibration of cognition.

The abyssal descent, as lamented in Psalm 42:7-8 (cf. Jonah 2:2-6; Lam. 3:55; Job 23:10; Isa. 43:2), refines the ψυχή through affliction, prefiguring Isaiah 43:2’s assurance that this trial is not annihilation but transformation.

The kenotic effacement of ego, as in Philippians 2:7, precedes divine plenitude, mirroring Ecclesiastes 1:9, in affirmation of existence as a recursive crucible of wisdom.

The nous, shaped through prefrontal-limbic entrainment, descends into dissolution, where Bayesian inference restructures perception until, in Wisdom 9:17, the self is subsumed into divine wisdom, completing the metamorphic cycle.

See Israel’s Babylonian exile and return (cf. Cyrus Cylinder).

Under existential threat, belief refines into actionable faith, while mystical traditions transcend intellect, embedding intuition within neuropsychological altered states.

Émile Durkheim in The Elementary Forms of Religious Life, posited that religious beliefs and practices serve to unite individuals into a single moral community, thereby enhancing social solidarity:

Human nature is the result of a sort of recasting of the animal nature, and in the course of the various complex operations which have brought about this recasting, there have been losses as well as gains….

Now in order to maintain itself, society frequently finds it necessary that we should see things from a certain angle and feel them in a certain way, consequently it modifies the ideas which we would ordinarily make of them for ourselves and the sentiments to which we would be inclined if we listened only to our animal nature…

…it is a vain enterprise to seek to infer the mental constitution of the primitive man from that of the higher animals (66).

Human nature emerges from a reshaped animal nature, where societal forces refine perception and emotion, distancing us from instinct and rendering direct comparisons to primitive cognition futile.

This situates belief within contingency rather than necessity, where the notion of Dieu sans l’Être aligns with the paradow of qadar (Al-Insan, 76:30): free will exists, yet it is already enfolded within divine predestination.

Faith isn’t just about certainty—it’s a deep, personal struggle (chaos-struggle) where people wrestle with doubt and paradox.

Like Kierkegaard’s Knight of Faith, they must take a leap beyond logic into trust.

This struggle is part of a sacred process, where belief (credo) and mystery (mysterium) constantly shape and challenge each other, much like a fire that refines and transforms.

Hans-Georg Gadamer's argument that understanding is always shaped by prejudgment (Vorurteile), meaning that all knowledge is mediated through prior beliefs, traditions, and historical context, is discussed in Wahrheit und Methode.

Gadamer refutes the Enlightenment’s rejection of prejudice as itself a bias against tradition, asserting that understanding is inherently shaped by inherited meanings and cultural preconceptions, making interpretation a continuous dialogue between past and present.