A little bit of knowledge Can be a dangerous thing; Or it can be a vibrant seed Giving rise to verdant forests And awakening sleeping giants.

— Chan Thomas, at the end of The Adam and Eve Story, which reminds me of a quote by James Hollis regarding projection1

Ancient frescoes and relief are alive, with vivid depictions of nature and humanity intertwined—a threshold that beckons us into a forgotten world— where time slips away.

The pulse of life in these works hums beneath every surface, as past and present converge, to emerge whispered stories that stir something deep within our collective structures and psyches.

They capture our experiences (of those long gone, but still with us), a call upon a reconnection with timeless beats that still rhythm our existence, unseen, beneath the stars2.

As you step into the ancient world, can you feel the pulse of something greater and timeless, calling you to remember what’s forgotten?

Times invitation by guardians

The Spring Fresco from Akrotiri, Thera (Santorini), is a stunning relic of Minoan civilization.

From the 16th century BCE, it celebrates the pure vitality of nature, filled with blooming lilies, swaying reeds, and darting swallows, capturing a world where life flourishes in the absence of humanity.

This fresco is more than just an image of nature—it embodies the flirtatious essence of life itself—where transformation meets imagination, carried in the philosophies of Giordano Bruno and Ibn Arabi.

Giordano Bruno, a 16th-century philosopher, believed in an infinite, living universe, found in the reflected, dynamic lines of the Spring Fresco3.

The movement within the artwork mirrors the vast, interconnected cosmos, alive with divine presence, drawing the viewer into the same boundless freedom embodied by the soaring swallows, reminding me of Wahdat al-Wujud (the unity of existence), described by 12th-century Sufi mystic, Ibn Arabi4.

The blooming flowers, swaying reeds, and darting birds within the Spring Fresco represent the harmony of all life—flowing together as part of a unified, sacred existence—reminding us that everything is woven into the interconnected fabric of the universe.

Forgotten voices of the timeless, present mind

The Menna and Family Hunting in the Marshes, from the Tomb of Menna (1400–1352 BCE), crystallize the prismatic gossamer of chrysalis strokes breathed by ancient Egyptian life, to unfurl more than a timeless entanglement where breath meets wilderness.

Birds glide above, fish dart below, and the papyrus sways in unison with unseen rhythms, becoming a choreography of primal pursuits threading mortality’s delicate surrendering—to the membrane between emergence and dissolution—as ontological rebirths converge, fragmentary perceptions of a dissolved wholeness interlaced in polymorphic boundaries and ecological poetry.

Here, freedom takes wing with the birds, abundance courses with the fish, and life unfurls through the ever-shifting marsh.

The water, central to this tableau, becomes a symbol of transformation, an archetype recurring across cultures as a metaphor for life, fertility, and the depths of the unconscious.

In Lions in a Garden, the reclining lion, emblematic of strength and embodying Carl Jung’s shadow integration, mirrors the balance between primal force and tranquil wisdom found in Menna and Family.

To re-forge our bond with the earth and its inexorable patterns, to rediscover meaning in shared existence, the depiction of fish, birds, and water reconcile and sustain the equilibrium of both life and self-awareness, the primal urge to reconsider our disconnection from the natural world estranged from cyclical truths5.

These frescoes beckon us to elemental instinct, the intricate participation neither above nor apart from existence, as the filaments of persistence undulate the mandala of palimpsest biology.

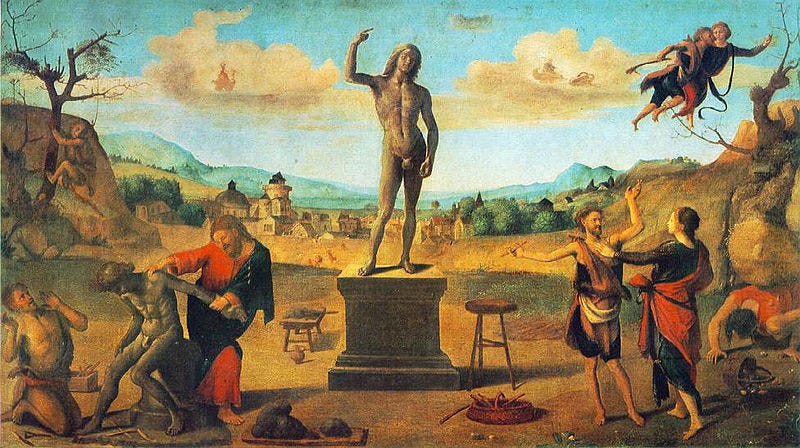

Sacred actions that overlooked Prometheus

As the path winds deeper, you reach a clearing where a bright fire burns, surrounded by familiar faces and strangers alike, all sharing a look of contemplation, for this fire offers more than warmth.

It’s a place where thoughts turn to deeds, and action speaks the knowledge you’ve gathered, and as the fire crackles with flames licking the air, you realize this journey is not just about lofty ideas or beautiful stories.

The sparks flying up into the night sky are moments in your life, transformed into practical use, where wisdom takes root:

when you choose to be present in a conversation

when you breathe deeply instead of reacting out of stress

when you apply resilience in the face of failure

The forest reveals that in the messy reality of life, there’s a fire that carries the flame of action, one small step at a time.

Root-song: An Ecological Psalm

As we step beyond the forest’s edge, there lies a quite root:

the forest is not a place you leave behind, but a living connection you carry within.

Its rhizosphere tendrils braid themselves in lambert penumbral realms, a living tessellations of translucent corridors of connection, breathing the symbiotic vitality of constellations reciprocal intelligence, trembling a sentient cathedral of perpetual meridians through permeable ichor coursed in ligneous understanding.

The forest endures, unyielding and eternal, its essence woven into the fabric of your being. Its whispers steady you when life grows loud, guiding you with the flame you bear—illuminating not only your path but the way for others seeking their own answers.

Though you walk beyond its shade, the forest remains within you—its timeless wisdom, ancient and resonant, a quiet journey back to yourself and a beacon for those who walk beside you.

Together, you make the forest thrive, a symbol of enduring truth, shared growth, and the unbroken connection between all who seek its boundless wisdom.

How might rekindling the long-dormant and ceaseless pulse within our collective nature lead us to a more primordial awakening, of our intrinsic interconnectedness, and the sacred purpose we hold within the vast, unfolding cosmos?

James Hollis discusses the fourth and fifth stage of projection (realizing reality contradicts our fantasy and becoming aware of projection itself), in Finding Meaning in the Second Half of Life: How to Finally, Really Grow Up.

The passage reads:

Every failed projection is a quantum of energy, our energy, an agenda for growth or healing, and a task that has come back to us. Can we bear to take the step to own the projection, see that its agenda may not be realistic, may be infantile, may not have legitimacy when flushed out of hiding, and then redirect our lives more fully, more responsibly? … We seldom know ourselves well enough, are seldom strong enough, or conscious enough, to attend this task on a permanent basis. There are many places in the psyche of each of us that seek aggrandizement, healing, reinforcement, or even satisfaction of what Freud called “the repetition compulsion,” the magnetic summons of an old wound in our lives that has so much energy, such a familiar script, and such a predictable outcome attached to it that we feel obliged to relive it or pass it on to our children (81).

Both Hollis and the quote reflect on knowledge, and highlight that self-awareness—whether confronting projections or gaining knowledge—can either perpetuate harmful patterns or serve as a catalyst for transformative growth, depending on how we engage with it.

I am reminded of the Latin phrase: "Astra monent, non inclinant," meaning, "The stars remind us, but they do not incline us."

This reflects a philosophical extension of the well-known medieval astrological saying, "Astra inclinant, sed non obligant" ("The stars incline us, they do not compel us").

The phrase encapsulates the belief that while celestial bodies—stars and planets—may influence human tendencies and behavior, they do not dictate our fate or compel our actions, reaffirming the existence of free will and underscoring that, although fate may offer subtle guidance, we are ultimately accountable for our own choices and the paths we follow.

Giordano Bruno’s belief in an infinite, living universe is detailed in On the Infinite Universe and Worlds (1584) and The Ash Wednesday Supper (1584), where he proposed a cosmos without a center, filled with countless, life-filled worlds.

[For more information about Bruno, and his theories, read the Library of Congress article Stars as Suns & The Plurality of Worlds, as well as Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy’s article Giordano Bruno]

The concept of Wahdat al-Wujud (Unity of Existence) is found in Ibn Arabi’s works, particularly Fusūs al-Hikam (The Bezels of Wisdom) and Al-Futuhat al-Makkiyya (The Meccan Revelations), where he explains the interconnectedness of all existence through the divine essence.

Such imagery and vision aligns with Roberto Assagioli’s theory of the transpersonal self and Marie-Louise von Franz’s mythological studies of the unconscious.

Assagioli posited that each individual psyche connects to a greater whole, a universal fabric linking humanity to the cosmos, while von Franz’s work unveils the archetypes that shape human existence, inviting us to see ancient myths—and these murals—as mirrors of universal truths.