Do not wait. The time will never be "just right." Start where you stand, and work with whatever tools you may have at your command, and better tools will be found as you go along.

— Napoleon Hill, Think and Grow Rich

Every business begins as a tenuous trembling buried beneath the sediment of hesitation.

I’ve tried to start my own business, and let me tell you, it has been a failure.

Not only am I unable to secure clients, but I don’t even have anything to sell, aside from the information I possess that is readily available for anyone given enough time and internet access.

The accessibility of information in the digital age means creators need to be more innovative, delivering more bang for the consumers buck, and as I’ve stood at the void, it’s all talk, plans, and dreams wafting into delusional fantasy, where my own ambition asks the question haunting me:

Am I enough?

The Ecosystem of Markets

[For more about market ecosystems, see Allegoria ed effetti del Buono e del Cattivo Governo]

Markets, at their core, are living systems, thriving not only on goods but on relationships, reputations, and risk.

Commerce, in its infancy, was not the mechanized leviathan of today, but rather a behemoth of barter in sunlit marketplaces—an exchange of goods, services, and trust.

The earliest known market systems come from Mesopotamia, but they’re specific names aren’t akin to modern “marketplaces,” often referred to as karum (Akkadian for “quay” or “harbor”) in regions such as Assyria and Anatolia1.

Before currency, there were cowrie shells; before banks, there were the merchant assemblies of the Phoenicians, pooling resources and mapping seas yet unknown.

Even the agora of ancient Greece, famed for its intellectual debates, functioned as an economic hub—a space where the clink of coins underpinned philosophical discourse.

These were the scaffolds of capitalism, built on ingenuity and the audacity to innovate in the face of scarcity2.

Today’s entrepreneurs, with their instrumentum digitalis, are imbued in the same machinations animated to commercialism—res materialis et magistri antiquitase—delineates innovation, as flickering minds once pioneered the Venetian traders towards Anatolia, weaving both textiles for commerce, and hands of foundations.

Embers and Enterprise

The mythos of expertise, like Piranesi’s Carceri d’Invenzione, constructs an endless architecture of aspiring self-doubt, where wanders among shadowed staircases spiral into seeming infinity3.

Expertise is not the forbidding acmé of an unsalable peak, but the ignis fatuus—a transient glimmer, as ancient as the potter’s wheel and as fundamental as the ink-stained manuscripts of a medieval scriptorium—enough to illuminate paths obscured by uncertainty.

From the blacksmith imparting the first strike of the hammer to apprentices, to the herbalist preserving remedies born of lived wisdom, and the Roman wine merchant selecting amphorae that whispered of quality, the timeless choreography of craft, trust, and ingenuity endures.

Automation is not the enemy of creativity but its enabler, freeing time for innovation and connection, similar to the kintsugi artisan transformation of broken vessels into storied resilience, or how AI, like Watt’s steam engine, liberates human potential from monotony to create new realms of creativity and wisdom.

The Eternal Market

Commerce, that eternal chiaroscuro of desire and provision, resonates in the intricate weaving of amor, ars, et pretium—a trinity echoing through history’s annals4.

The 13th-century silk merchant navigating the vast trade networks of the Mongol Empire, hermeneutically articulated in Marco Polo’s Travels intuitively synthesized within the noumenal (the ontological coalescence of value) akin to the Summa Theologica’s reflections on commerce, heuristically culling logocentric filaments that glisten in the eyes of distant buyers, a dynamic instantiated in the Tabula Rogeriana and the Hereford Mappa Mundi, where trade routes charted not only physical exchanges but also metaphysical convergences of culture and meaning.

This ordo commercii finds its mirror in the where trade routes charted not only physical exchanges but also metaphysical convergences of culture and meaning, as earlier depicted in the works of Ptolemy and Roman and Sassanian texts, a silent tension of Morton Feldman’s Triadic Memories.

Automation, like Maillardet’s automaton écrivain, functions as an instrumentum rationis, amplifying potentia humana, as Feldman’s notes compose reflections evoked in dialectica penuriae et copiae5.

The entrepreneurial journey, as a via doloris (path of suffering), mirrors the Hegelian dialectic where each Scheitern serves as an act of creation sculpting the Seele through negotiation and repeal, ultimately transmuting despair into renewal and vision6.

The Waste Land

The epigraph to The Waste Land, drawn from Petronius’s Satyricon, depicts the Sibyl of Cumae, a prophetic figure cursed with immortality but not eternal youth, lamenting her endless existence and yearning for death.

The Sibyl’s plight in Eliot’s poem symbolizes a world burdened by knowledge and progress yet devoid of meaning, reflecting the spiritual and cultural disillusionment and post-World War I fragmentation of modernity.

The dedication to Ezra Pound as “il miglior fabbro” (the better craftsman), borrowed from Dante’s Purgatorio, acknowledges Pound’s crucial role in refining Eliot’s sprawling manuscript into a cohesive masterpiece.

To embark upon the founding of a business is to engage in the modernist quest for meaning amidst cultural decay, weaving oneself into the grand tapestry of human creativity—a lineage as ancient as the reciprocal gifting of obsidian tools in Paleolithic times and as forward-looking as the decentralized ledgers of blockchain technology7.

The act of building a business is akin to constructing a suspension bridge that spans the chasm between the ideal and the real; it is to enter the agora, the locus of dialogue and exchange, where trust operates as the primordial currency, the ars poetica of innovation’s progression, enduring and ennobling trust, value, and resilience in all acts of enterprise8.

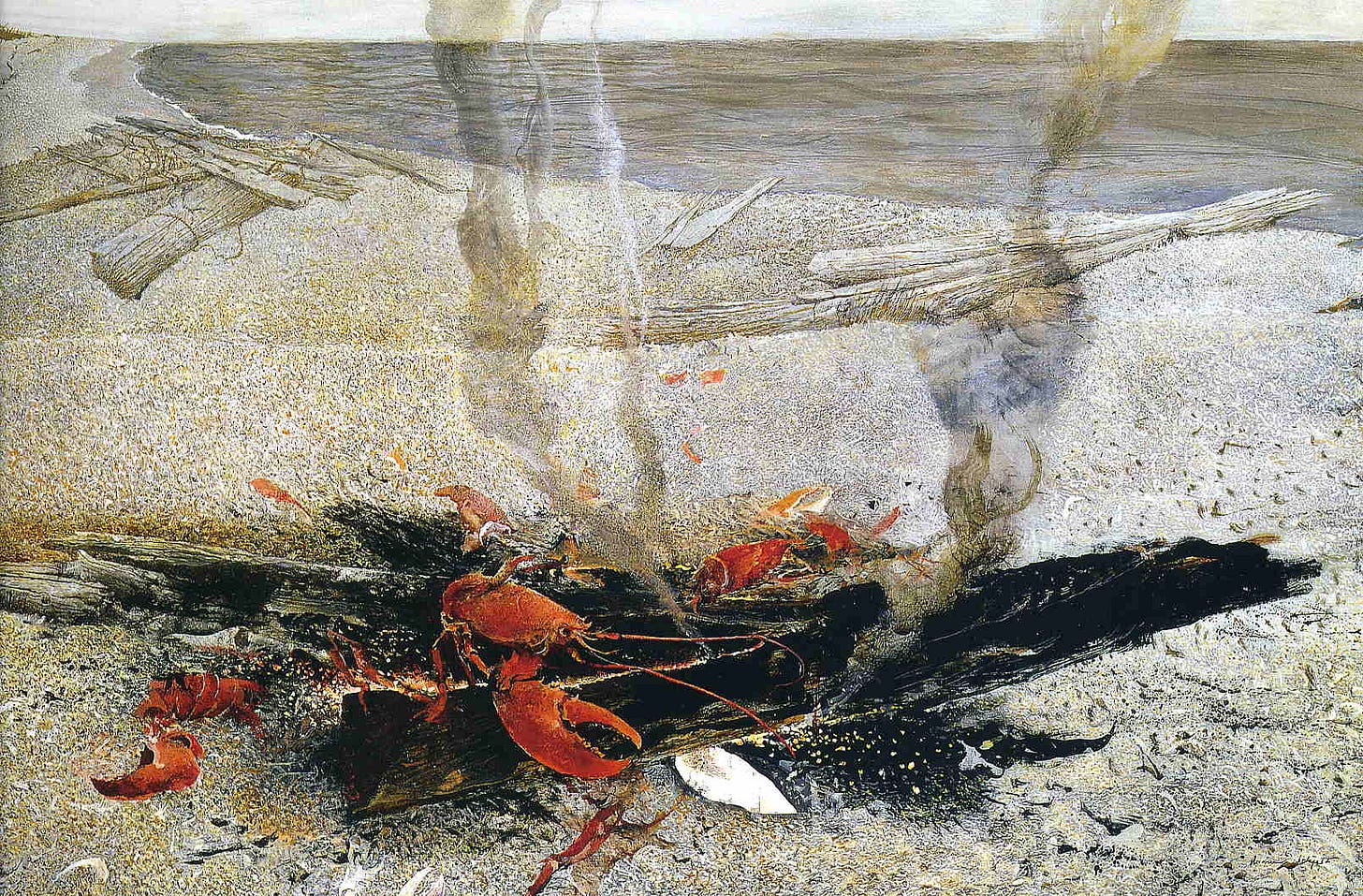

The Alchemist Discovering Phosphorus

The market unfolds the capricious yet fecund tableau of Baroque Wunderkammer, where risk and opportunity dance in a delicate counterpoint to evoke the chiaroscuro drama of Joseph Wright’s explorations of illumination and shadow.

The entrepreneur, both artist and alchemist, transforms instability into innovation, reflecting Prigogine’s theory that order arises through chaos, a corroborative summary of Genesis 1:1-3, revealing divine or natural forces shape emergence in creation.

To construct a bridge—not toward a fixed destination but to an ever-shifting horizon of potential—embodies an existential defiance of stasis, the imaginative spirit of Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Dialogues or Mandelbrot’s fractal geometric patterns, leveraging the architecture of possibility no longer confined to oligarchic dominion but to those who dare to wield them.

Thus emerges the custodian of ceaseless ingenuity, found in the works of Renaissance scientist Giambattista della Porta, whose Magiae Naturalis, unveiled latent potential within the iterative process of deconstruction and renewal: solve et coagula.

They illuminate pathways for future seekers, ensuring that the eternal flame of enterprise continues to burn, a beacon of creativity and resilience in an unpredictable world.

What tools, tangible or intangible, do you already possess that could spark a transformation in your life or work, and how might the act of beginning itself reveal resources you never imagined you had?

Highcock, N. (1 C.E., January 1). The Old Assyrian Period (ca. 2000–1600 B.C.). The Met’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Capitalism, rooted in structured trade systems, philosophical frameworks, financial innovations, and societal shifts such as labor displacement and the rise of merchant classes, evolved from localized subsistence economies into a profit-driven system characterized by private ownership, wage labor, and global expansion, with its modern form shaped during the Industrial Revolution and defined by thinkers like Adam Smith and critics like Karl Marx.

The historical development of capitalism draws upon numerous precursors.

Early examples include the Laws of Eshnunna (c. 1930 BCE), which standardized wages and trade in Mesopotamia, and Kautilya’s Arthashastra (4th century BCE), an Indian treatise promoting economic planning and state involvement.

The Tang Dynasty (7th century CE) implemented market regulations to stabilize trade, while Venice (14th century) developed contract-based commerce, including risk-sharing partnerships.

Coastal Swahili city-states (10th–15th century) established affluent trade networks, and the Fuggers of Augsburg (15th–16th century) innovated international banking.

Islamic waqfs (7th century CE onward) introduced asset management systems, and Ming Dynasty paper money (14th–15th century) exemplified advanced credit systems.

These diverse contributions collectively shaped the foundations of modern capitalism.

The myth of Daedalus is recounted in Ovid’s Metamorphoses (Book 8), Apollodorus’ Bibliotheca (Book 3, Chapter 1), and Plato’s Timaeus (26b), where Daedalus is both a creator and symbol of human ingenuity.

His tragic story is also referenced in Virgil’s Aeneid (Book 5).

Commerce, often described as the interplay of light and shadow (chiaroscuro), reflects the balance between desire and provision, captured in the trinity of amor (love), ars (art or craft), and pretium (price or value).

This concept has echoed throughout history, symbolizing the relationship between human aspiration, the skills employed to fulfill needs, and the value ascribed to goods and services.

This trinity is a recurring theme in economic, philosophical, and artistic discourses, emphasizing the dynamic and complex nature of exchange, both material and immaterial.

The phrase dialectica penuriae et copiae, meaning "the dialectic of scarcity and abundance," encapsulates the dynamic tension between penuria (limited resources) and copia (plentiful supply).

It is a concept resonant in the negotiation of opposing forces that shape human systems and experiences. Gutenberg’s ars impressoria (art of printing) and modern automata cogitandi (thinking machines) transcend the monotony of repetition, unveiling a palimpsestus—sparse, infinite parsecs of Unendlichkeit (boundless creative space)—where the interplay of limitation and expansiveness unfolds across disciplines.

In Phenomenology of Spirit, Hegel outlines the dialectical process where contradictions and suffering lead to self-transformation and higher understanding.

In the section on Self-Consciousness, particularly the master-slave dialectic, he shows how failure and negation (such as the slave’s suffering) drive progress toward self-realization.

This theme continues in the Reason section, where the individual's struggles with certainty and self-certainty ultimately lead to absolute knowing.

The process of negation and aufhebung (sublation) reveals how despair and contradiction are necessary for the development of consciousness and spirit.

Founding a business is the modernist quest for meaning amidst cultural decay, paralleling the ancient exchange of obsidian tools extending towards blockchain technology outlining a partnership where one party provides capital and the other labour, balancing risk and reward.

This balance reflects the epistemic humility seen in the speculative machines of Athanasius Kircher, whose designs embodied the creative forces that also underlie the metaphysical scaffolding of entrepreneurial creation.

This endeavor reflects Giambattista Vico’s corso e ricorso, where resistance and creativity are mutually generative forces, with each effort, failure, and iteration serving as a synecdoche of human striving, a small yet significant part of the whole.

What a rich and illuminating gem of a piece. I thoroughly enjoyed this, and found it very well researched and insightful.

Keep up the fine work!